Cham b'Tverya

- Mike Levitt

- Aug 3, 2018

- 17 min read

A well-known Hebrew expression, cham b'Tverya ("it's hot in Tiberias"), indicates a general exasperation with never-ending heat and humidity during the long coastal and Tiberian summers. So it was a little crazy of us to spend a few days there in August―but that's what we did! We stayed in a zimmer (B&B) in the Old Town, just next to the Ottoman citadel or fortress: Villa Alliance.

Itself of historic interest, Villa Alliance is a converted nineteenth century basalt building which, between 1925 and 1940 served as the Alliance School, being the first Jewish school outside the city walls. The elementary school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle was however already established earlier: the boys’ school opened in 1897 and the girls’ in October 1900. Children learnt French and Hebrew there and, by 1903, enrolled 320 pupils out of Tiberias’ 4,000 Jewish residents, a very large percentage. You can read more about the Alliance's Schools in Palestine and Syria between the 1870s and the 1900s here.

Villa Alliance, the former Alliance School at Tiberias.

The city of Tverya (טבריה), known in English as Tiberias and Arabic as Ṭabariyyah (طبرية), with a population today of about 30,000, was established around 20 CE, by Herod Antipas, son of Herod the great. Herod Antipas had been made Jewish ruler of the Galilee in 4 BCE by Augustus Caesar. He made the new city his capital, and named the city in honour of the second emperor of the Roman Empire, Tiberius.

However there had been a settlement in the immediate vicinity since biblical times. The Jewish town of Rakat, 2 km north of Roman Tiberias, is mentioned in the Book of Joshua (19:35), whilst Hammat, built around the hot springs to the south of the city, is mentioned in the Mishna and Babylonian Talmud. Bet Ma'on (Bethmaus)―whose location is today inside modern Tiberias―was a Jewish village during the late Second Temple and Mishnaic periods. The Midrash (Genesis Rabba § 85:7) says of the village, "Beth Maʿon, they ascend to it from Tiberias, but they go down to it from Kefar Shobtai." The Jerusalem Talmud, citing a variant account, says that they would go down to Beth Maʿon from its broad place. Those fascinating sites are for future blogs.

The staircase leading from Villa Alliance to the shore of the Kinneret

"Modern" Tiberias―meaning Ottoman Tiberias (the "Old City") and 20th century Tiberias―are to the north of the Roman city.

Tiberias was held in great respect in Judaism from the middle of the 2nd century CE, tradition holding that Tiberias was built on the site of Rakat, and in Talmudic times Jews still referred to the city of Tiberias as Rakat. The Roman city was built in immediate proximity to the spa which had developed around 17 natural mineral hot springs at Hammat, which eventually became a southern suburb of the new city. Tiberias was at first a strictly pagan city, but became a mixed city after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, when Judean Jews moved north to the Galilee. In 145 CE, Rabbi Simeon bar Yochai, "cleansed the city of ritual impurity", following which the Jewish leadership resettled there from Judea , where they were fugitives. The Sanhedrin―the High Court of Israel during the period of the Second Temple―also fled from Jerusalem during the Great Revolt, and after moving around several Galilee towns, settled in Tiberias in about 150 CE, its final location before its disbanding in the early Byzantine period.

From the 2nd to the 10th centuries, Tiberias was the largest Jewish city in the Galilee and the political and religious hub of Judaism in Israel; when Johanan bar Nappaha settled in Tiberias in the 3rd century CE,, the city became the focus of Jewish religious scholarship in the land of Israel. The Mishnah, the collected theological discussions of generations of rabbis, primarily in the academies of Tiberias and Caesarea, was completed in Tiberias in 200 CE under the supervision of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi ("Judah the Prince"), and the Jerusalem Talmud was compiled in 400 CE. The Arabs conquered Tiberias in 634 CE. After his death in 1204, the great Jewish sage Maimonides was buried in Tiberias where his tomb may be found until today on Ben Zakkai Street. The street's namesake, Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai, is also believed to be buried nearby, and the tomb of Rabbi Akiva is also in the town. A Samaritan center existed in Tiberias in the middle of the 4th century CE.

During the First Crusade Tiberias was occupied by the Franks and the city was given in fief to Tancred, who made it his capital of the Principality of Galilee in the Kingdom of Jerusalem; the region being known as the Principality of Tiberias, or the Tiberiad. In 1099 the original site of the city was abandoned, and settlement shifted north to the present location within the modern city known as the Old City. St Peter's Church, though much altered and rebuilt, was originally built by the Crusaders, and various other Crusader remains can be seen.

Today's St Peter's Church, on the shore of the Kinneret, was constructed on the ruins of a Crusader church that had one nave and narrow windows similar to portholes representative of the hull of an overturned boat

In 1187, Saladin ordered his son al-Afdal to send an envoy to Count Raymond of Tripoli requesting safe passage through his fiefdom of Galilee and Tiberias. Raymond was obliged to grant the request under the terms of his treaty with Saladin, and Saladin's force left Caesarea Philippi (Banias) and engaged the Knights Templars, defeating them, before going on to besiege Tiberias, which fell after six days. On July 4, 1187 Saladin defeated the Crusaders coming to relieve Tiberias at the Battle of Hattin, 10 kilometres to the west. Although, during the Third Crusade, the Crusaders drove the Muslims out of the city and reoccupied it, in 1265 it fell to the Mamluks, who ruled for 250 years until the Ottoman conquest in 1516.

Rabbi Moses Bassola visited Tiberias during his trip from Italy to Palestine in 1522. He wrote that Tiberias "was a big city... and now it is ruined and desolate [with] ten or twelve" Muslim households. The area was dangerous "because of the Arabs," and in order to stay there, he had to pay the local governor for his protection. During the Inquisition, many Sephardi Jews fled to Palestine, encouraged by Sultan Selim I. In 1558, a Portuguese-born marrano, Doña Gracia, was granted tax collecting rights in Tiberias and its surrounding villages by Suleiman the Magnificent. She worked for the town to become a refuge for Jews, and obtained a permit to establish Jewish autonomy there. In 1561 her nephew, Joseph Nasi, encouraged Jews to settle in Tiberias and, securing a firman from the Sultan, he and Joseph ben Adruth rebuilt the city walls and laid the groundwork for a silk industry, planting mulberry trees and urging workers to move there. However plans for Jews to move from the Papal States were abandoned when the Ottomans and the Republic of Venice went to war. Tiberias became a largely Jewish city and, since the 16th century, has been considered one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Hebron and Tsfat (Safed).One of the leading members of the Tiberian masoretic community was Aaron ben Moses ben Asher, who refined the oral tradition now known as Tiberian Hebrew.

This sculpture of limestone and basalt, celebrating (and called) Tiberias Vowel System, is by David Fine (2008). The Tiberias vocalisation of Hebrew was based on the traditional Tiberias vowel system. After this system became the authoritative one for Torah reading, the others fell into disuse.

The destruction of Tiberias by the Druze in 1660 resulted in abandonment of the city by its Jewish community. In the 1720s, the Bedouin ruler, Daher El-Omar, fortified the town and signed an agreement with the neighboring tribes to prevent looting. Accounts from that time tell of the great admiration people had for El-Omar, especially his war against bandits on the roads. Richard Pococke, who visited Tiberias in 1727, witnessed the building of a fort to the north of the city, and the strengthening of the old walls, which can still be seen today.

The Fortress (citadel)―erroneously named the 'Crusader castle'―was actually built in 1745 by Chulaybee, son of Daher El-Omar, the Bedouin ruler of the Galilee. It is part of the Ottoman wall encircling the old city. The two storey structure with four corner towers was built using reclaimed basalt masonry from earlier structures.

Reclaimed basalt masonry from earlier Jewish structures incorporated in the Fortress wall: rosette (left) and Byzantine-era menora (right)

Under El-Omar's patronage, Jewish families were encouraged to settle in Tiberias, and he invited Rabbi Chaim Abulafia of Smyrna to rebuild the Jewish community. The synagogue Rabbi Abulafia built still stands today, located in the former Court of the Jews. The synagogue became a spiritual centre for many generations of scholars, and was given the Aramaic name "Knishta Raba" (Great Synagogue). Before the various rebuildings, it was considered the prettiest synagogue in the country. Today it is known as the Etz Chaim or Abulafia synagogue.

The Etz Chaim (or Abulafia) Synagogue, established in 1742 by Rabbi Chaim Abulafia on the site of earlier synagogues. Abulafiah immigrated to Tiberias from Istanbul in 1740, at the invitation of Daher al-Omar. The synagogue underwent major reconstruction following the earthquakes of 1759 and 1837 and the great flood of 1934. According to tradition, this is the synagogue where the Holy Ari used to pray and the Sanhedrin met.

In 1780, many Polish Jews settled in the town and, during the 18th and 19th centuries, an influx of rabbis re-established the town as a centre for Jewish learning. Rabbi Chaim Shmuel HaCohen Konverti, a wealthy and learned Jew from Spain, came to Israel in 1827, settling in Tiberias. After the earthquake of 1837, he built a synagogue, a Judaica library and a new home in the Court of the Jews. He was a driving force in the restoration of the city.

The ruins of the El Señor Sephardic synagogue. El Señor refers to Rabbi Chaim Shmuel HaCohen Konverti, a wealthy and learned Jew, who came to Israel in 1827. After the earthquake of 1837, he built this synagogue, a Judaica library and a new home in the Court of the Jews. When Konverti passed away, his daughter and son-in-law, Rabbi Yaakov Sha’altiel Niñio, moved into the house, where the family lived until 1981.

Tiberias has been severely damaged by earthquakes since antiquity, since it lies on the Dead Sea Transform. At least sixteen earthquakes are known to have occurred between 30 CE and 1943. The Galilee earthquake of 1837 killed 600 people, of whom nearly 500 were Jews.

Tiberias, April 22nd 1839, lithograph of a painting by David Roberts, RA [Public Domain]

Several other structures remain today in the former Court of the Jews. The Karlin-Stolin Synagogue was founded by the Karlin-Stolin Hasidim who arrived in the Holy Land in the mid-19th century. They settled in Tiberias, Hebron and Safed and, in 1869, they redeemed the site of a former synagogue in Tiberias. Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk―one of the leaders of the Chassidic movement, who emigrated in 1765 from Eastern Europe together with a group of several hundred followers―and Rabbi Abraham Kalisker built the synagogue in 1786. It was destroyed by the Galilee earthquake of 1837; construction of a new synagogue started in 1870. On one side of the complex is house of Rabbi Menachem Mendel, during whose residence Tiberias became known as one of the four “Holy Cities,” along with Jerusalem, Hebron, and Safed. The former house is now part of the Synagogue.

The Old Synagogue (now the Chabad Synagogue) was built by the Boyan Chasidim after the earthquake of 1837. The building remained deserted after the War of Independence, when the Chabad-Lubavitch Movement restored it.

The video below (courtesy Ottoman Imperial Archives) shows Tiberias from the Kinneret in 1916.

Next to the Etz Chaim (or Abulafia) Synagogue are the excavated remains of the northern wall and gate of the Crusader-era fortress built during the First Crusade, after Tiberias was occupied by the Franks and given in fief to Tancred, who made it his capital of the Principality of Galilee in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The fortress fell in 1187 to Saladin's armies, and its ruins stood desolate for hundreds of years until they were covered with soil on which the Jewish Quarter of Tiberias was built.

Below is a slideshow of the area―hover over each picture to read its caption―plus see the pictures of the Etz Chaim and El Señor synagogues above.

Between the former Court of the Jews and the Kinneret , both north and south, a number of other ancient structures survive, including churches,, fortifications and mosques. You can see some of these in the slideshow below, hovering over each picture to read its caption.

The Hibernian influence

David Watt Torrance was a Scottish doctor and minister on a mission in Tiberias. He had graduated Bachelor of Medicine at Glasgow University in 1883 but, despite being offered a post at Glasgow Infirmary, he travelled to Palestine in 1884 and assisted in the inauguration of the Sea of Galilee Medical Mission. After further training in Egypt, Damascus and Nazareth, he returned in 1885 to Tiberias and opened a mission hospital, that accepted patients of all races and religions, in two rooms near the Franciscan monastery. It moved to its current, larger premises at Beit abu Shamnel abu Hannah―now Gdud Barak Street―in 1894, where there were 24 beds and 6 cots. Torrance was ordained in the Free Church of Scotland in 1895.

David Watt Torrance, 1908 [Credit: By Unknown - נתרם על ידי מר דייוויד ביירן, נכדו של מר טוראנס Contributed by Mr. David Byrne - Grandson of Mr. Torrance, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17120199]

In 1923 Torrance's son, Dr Herbert Watt Torrance, was appointed head of the hospital. Herbert Watt Torrance―like his father―was educated at Glasgow University, graduating MB in 1916. He served in the Royal Army Medical Corps in France and Serbia during the Great War, and was awarded the Military Cross. After demobilisation he returned to Glasgow University as demonstrator and lecturer and to study for the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons. In 1921 he was awarded the degree of MD before moving to Tiberias, to join his father. He was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons and was awarded the OBE for services rendered during the British Mandate in Palestine. He married twice and had two daughters.

A church was opened in the compound in 1930; it still exists on Yigal Alon Promenade. After the establishment of the State of Israel, the hospital became a maternity hospital supervised by the Department of Health; Herbert Torrance retired to Dundee in 1953 and died in 1977. After the hospital's closure in 1959, the building became a hospice for travellers―known as the Scottish Hospice―and a resident minister and bookshop continued the work of Scottish Mission in Tiberias.

Herbert Watt Torrance was interested in photography. The Torrance Collection at the University of Dundee provides a record of the main period of the British Mandate, the increasing rate of Jewish immigration and the impact of the State of Israel on the landscape. It also contains many photographs of medical conditions which subsequently have been eradicated. Dr Torrance's interest in flowers, animals and archaeology is well represented and many photographs show examples of the "biblical situations" popular with photographers. The collection also contains a number of G. Eric Matson and Felix Bonfils photographs; one of Matson's is shown below.

Left: Entrance to The Scots Hotel (former entrance to the hospital) today.

Centre: Scots Mission Hospital, exterior with new garden in front, early 1940s [Credit: By Matson Photo Service, photographer - This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID matpc.12881. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36685561]

Right: Dr David & Herbert Torrance Square, 1962, formed from the gardens of the former hospital.

Left: Erected in memory of Eliza Reid of Belfast by her Sister in 1896, Lakeview served originally as an orphanage to care for street children and orphans of all races and religions in the area, with accommodation downstairs and teaching upstairs. After fifty years it served as a school for nurses employed in the neighbouring Scots Hospital. In the late twentieth century, it provided accommodation for pilgrims and volunteers, and administration offices for the Guest House. It is now a spa, unconnected with the hotel.

Right: Lakeview, early 1940s [Credit: By American Colony (Jerusalem). Photo Dept., photographer - This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID matpc.11455. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36692937]

A little Jewish boy patient in the Scots Mission Hospital, 1930s [Credit: By American Colony (Jerusalem). Photo Dept., photographer - This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID matpc.03640. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36575849

In 1999, the former Scots Hospital was renovated at the cost of around £10,000,000―a controversial decision within the Church of Scotland, as you can read here, where there are more archive pictures―and reopened as the Scots Hotel in 2001.

Left: The Scots Hotel: the former main hospital building.

Centre: The Scots Hotel; the middle building was the doctors' residence.

Right: The Scots Hotel from the north. In the foreground can be seen a watchtower sporting a flaccid Scottish flag in the still humidity. The tower is a remnant of the Ottoman city walls.

St Andrew's Church of Scotland, built in 1930, part of the Scottish Compound, it is one of only two Scottish churches in Israel, the other being St Andrew’s Scots Memorial Church in Jerusalem. The church can hold 130 people and is also used by The Scots Hotel as a venue for concerts. The upper floor of the building is currently occupied by a small Messianic Jewish elementary school.

Arab hostility and evacuation

During the British Mandate, the relationship between Arabs and Jews in Tiberias was relatively good, with few incidents during the unrest of 1929. In Tiberias that year the first modern spa was built. However in October 1938, Arab militants massacred nineteen Jews, including eleven children, in the Jewish neighbourhood of Kiryat Shmuel, and murdered the Jewish mayor, Zaki Alhadeef a few days afterwards. Below you can see Haim Hatzav's film about the massacre (in Hebrew).

The modern town has been shaped by the great flood of 1934. Deforestation on the slopes above the town combined with the fact that the city had been built as a series of closely packed houses and buildings hugging the shore of the lake, meant that when flood waters carrying mud, stones, and boulders rushed down the slopes, they flooded the streets and buildings so rapidly that many people did not have time to escape. There was huge loss of life and property. The city rebuilt on the slopes above the old town, and the Mandatory government planted the so-called Swiss Forest on the slopes to hold the soil and prevent similar disasters from recurring. A new seawall was constructed.

Below is a film report―the first ever in Hebrew in the Land of Israel―of the 1934 flood, courtesy of The Spielberg Jewish Film Archive.

On the eve of Israeli Independence, Tiberias had a population of around 11,000, the majority of whom were Jews. The Arab population numbered about 5,700, the majority of whom were Muslims. During the time of the British Mandate people had begun to settle outside the Old City walls, with Jews and Arabs building both mixed and separate neighbourhoods. With the exception of the 1928 massacre, relations between Jews and Arabs in the town had been good and the town was known for its moderation. Thus it was unsurprising that in March, 1948 the Jews and Arabs of Tiberias forged a cease-fire. But the truce was short-lived and by 8 April, the Arabs started firing at the Jews, and the Haganah fought back, defeating the Arabs.

Only later did the deep tragedy of this event―which led to the total evacuation of Tiberias' Arab citizens―emerge. Fawzi al Qawugji’s ‘Arab Liberation Army,‘ created by the Arab League, which had infiltrated from Lebanon in January 1948 with little or no British opposition and now awaited orders to attack Tiberias. Tiberian Arabs had not wanted to fight the Jews―the local National Committee refused the offer of the Arab Liberation Army to defend the city―but a contingent of outside Arabs moved in, attacking the Jews from the local Arab homes. The local Arabs had even fought against the incomers, but in the end they were forced to leave. The British refused to intervene. Relative quiet reigned in Tiberias until 10 March 1948, when a rumour spread among the Arab population that a Jewish leader had been killed by Arabs and that the Jews were planning reprisal attacks. The Arabs opened fire and fighting continued for three days until a British-brokered ceasefire was agreed. The ceasefire held until 5 April 1948, when Arab gunmen opened fire on Jewish shoppers at the market, killing five elderly people and taking ten women prisoner. The Haganah responded, taking 12 Arabs prisoner, and fighting took place all over the town. Another British-brokered ceasefire resulted in an exchange of prisoners, after which the two sides marched together down Galilee Street to demonstrate their wish for peace. Under the influence of Mufti Haj Amin al Husseini's intervention, appointing the extremist Subhi family as leaders of the Arab forces in Tiberias, this ceasefire was short-lived too. On 8 April, Arab gunmen again opened fire on shoppers at the market and on Haganah positions, taking over the Scottish hospital and the Tiberias Hotel and blocking the main street of the town. British attempts to secure a ceasefire were unsuccessful and fierce fighting continued. With the local members of the Haganah exhausted from days of non-stop fighting, it was decided to send in additional troops including the Golani Brigade to try to bring an end to the fighting.

Several days of fierce battles followed. On the morning of 18 April, representatives of the Arab forces approached the British commander, Colonel Anderson, requesting to leave the town with their weapons. Anderson then summoned the town’s Jewish commanders and informed them that the British would be evacuating its Arab residents and that as of ten days later, British forces would leave Tiberias in Jewish hands―as indeed they did on April 28th 1948. The Jewish representatives asked Anderson that the Arabs simply hand over their weapons and that they not leave but, that afternoon trucks and buses began arriving in Tiberias and, under British supervision, the town’s Arab population was evacuated to Nazareth and to Jordan.

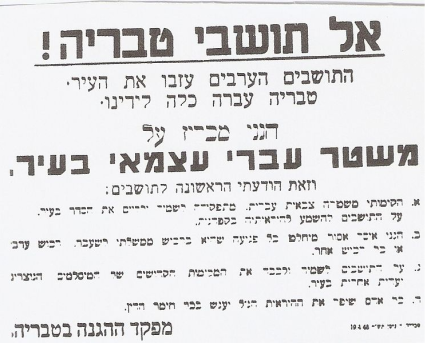

Yet even in the immediate aftermath of the Jewish victory, the Jews safeguarded the Arabs' abandoned homes from Arab looters, with the expectation that the Arab population would return, as can be seen from the newspaper article below.

Left: Palestine Post 19.4.1948; Right: Haganah announcement against looting Arab property

The Arab population of Tiberias (6,000 residents comprising 47.5% of the population) was evacuated under British military protection on 18 April 1948. An opinion piece in the Palestine Post told how Tiberias' Arabs had been used as pawns when the Jews had no general interest in pushing them out of their future state.

An understanding of the nuances of Israel's Arab-Jewish problem can be gained from such history as this. In researching this post, I came across the blog of the young Minister of St Andrew's Church in Tiberias―Reverend Kate McDonald―who came here from Edinburgh in 2015. I was struck by one piece in particular, in which I see the calm, civilised humility, respect and understanding that Israel/Palestine is not the black and white issue which most in the West feel is so easily solved, and for which we Jews suffer increasingly vitriolic and antisemitic attacks.

Tiberias today

The old city centered around the Court of the Jews―first modern Jewish quarter―built in 1740 with the help and support of Daher al-Omar, the Bedouin ruler, following Rabbi Chaim Abulafiah’s immigrated to Tiberias from Istanbul at the invitation of al-Omar. The neighbourhood was surrounded by a wall, forming a court which included synagogues, yishivaot (religious seminaries) and mikvaot (ritual baths), some of which still exist today. Ancient and mediaeval Tiberias was destroyed by a series of devastating earthquakes, and much of what was built after the major earthquake of 1837 was destroyed or badly damaged in the great flood of 1934; only houses in the newer parts of town, uphill from the waterfront, survived. For this reason it was decided, in 1949, that 606 houses―comprising almost all of the built-up area of the old Jewish quarter other than religious buildings―were demolished over the objections of local Jews who owned about half the houses. The area of the Court of the Jews is now a fairly barren plaza―HaZikaron Garden―containing a memorial to the fallen of Israel's wars, in addition to some archaeological remains and a number of religious institutions. The city of Tiberias has been almost entirely Jewish since 1948. Many Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews settled there in the 1940s and 1950s, and government housing was built to accommodate much of the new population, like in many other development towns. Wide-scale development began after the Six-Day War, with the construction of a waterfront promenade, open parkland, shopping streets, restaurants, modern hotels and tower blocks. These are very much in evidence today, rather tired and run-down in many cases, belying the interesting features of the town which remain. Hidden amongst this modern construction are several churches, including St Peter's―whose foundations date from the Crusader period, the city's two Ottoman-era mosques, and several ancient synagogues, which were carefully preserved at the time, though the mosques are now quite dilapidated.

Housing and commercial space typical of any Israeli development town. However this one on―HaBanim Street―is enlivened by a mural of older times.

Throughout the city can be found examples of Ottoman, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century architecture in black basalt. Below is a slideshow of some of these not already mentioned. As usual, hover to read the captions.

Over time, Tiberias has become a major tourist destination, with modern high-rise resort hotels being built for Christian pilgrims and internal Israeli tourism. And increasingly the ancient cemetery of Tiberias and its old synagogues also attract Jewish pilgrims. But from the poor state in which the town's heritage finds itself, this is almost despite the amazing history and architecture to be found. In recent years the city has been known for its air of dereliction, decline and missed tourism opportunities. An article in Haaretz in the summer of 2017 painted a pretty accurate picture through its headline and by-line alone: "Celebrating 2,000 Years, Tiberias' History Is Buried Under Garbage: Ancient bathhouse under weeds, beer bottles covering a mosaic. Archaeological sites around the city could have been tourist attractions, but many are abandoned and neglected."

But more than this, Tiberias seems to emphasize a problem which is evident―in variable degrees―throughout Israel. Though there are good examples of the excavation, study or preservation of Arab and Islamic sites in Israel―such as Khirbet Minim or an ancient mosque recently unearthed in the Negev―in many instances they are neglected or overlooked. In addition to the old mosques in Tiberias which remain neglected I have written about other sites―such as Al-Bassa', Khirbet Idmit, or Bar'am―whose neglect, or lack of explanation, only serves those who claim we ignore or gloss over the Arab and Islamic history of the country.

Nevertheless, for the day-tripper eager to find interest for himself, off the beaten track, there is still much of interest to be seen and explored.

Comments