Elizabeth Hotel - מלון אליזבת

- Mike Levitt

- Nov 11, 2020

- 13 min read

The Elizabeth Hotel, on the corner of Ahad Ha'am and Bialik Streets (number 3 on the latter) in the Kiryat Shmuel neighbourhood of Tiveria (Tiberias), was built between 1926 and 1929 by Shlomo Feingold and Elizabeth Palmer during the British mandate period. The complex―comprising a hotel and theatre―was named after his first wife, Elizabeth, and was sometimes Hebraised as Hotel Elisheva. Top British officials attended the gala opening in 1929.

Shlomo Feingold, man of mystery and acrimony

The above seemed a simple enough story to the forlorn shell of a building which Amber and I visited, in the guise of urban explorers, one quiet afternoon. We thought that was all there was to say. But there is no such thing as a simple story in this land of multi-layered history! Feingold’s is a strange and fascinating story.

Shlomo Feingold was born in the then-Polish shtetl of Derechin (today Dziarečyn) in 1865, one of seven children of David ben Yosef Feingold, a wealthy merchant, and Feiga, the daughter of Noah Chaim, the rabbi of Shtshutshin (now Ščučyn). Shlomo studied at the Volozhin (Vałožyn) Yeshiva and was ordained a rabbi but, at the age of twenty, he traveled to England, becoming involved in pseudoarchaeological cult of the British Israelites, who believe that the people of the British Isles are “genetically, racially, and linguistically the direct descendants” of the Ten Lost Tribes of ancient Israel. In 1888, in London, Shlomo married an orphaned Christian woman named Elizabeth Colville, who had been adopted by Margaret Alice Palmer. Palmer, born in 1845 in Oldham, was by then a wealthy public figure in her forties; she became attached to Feingold and financed his construction and cultural enterprises. Between 1891 and 1895 the three were in Paris, where Feingold published a journal, La Vérité, about British Israelism. In the winter of 1895-1896 the three set off for Israel.

In Jerusalem, Feingold became a wealthy merchant, but was treated with suspicion in the Jewish community, both because of his religious views and because of his unconventional personal circumstances whereby, though he was married to Elizabeth, she did not appear in public, and he ran his business enterprises in partnership with Palmer, an unmarried woman who lived with him and his wife. In addition, people believed he was a missionary, so that his various attempts to gain the trust of the community through philanthropic endeavours were met with hostility and suspicion. He tried to gain a license to continue his Paris newspaper, The Truth, but did not succeed at this time. A group of young people, styling themselves Bnei Yisrael, organized anti-missionary activities and, one night in June 1896, smashed the windows of his house. He was widely accused of being an apostate.

SY Agnon describes, in his famous novel about the Palestine of the Second Aliyah, Tmol Shilshom (Only Yesterday), Feingold―whom he refers to as HaMeshumad (the Apostate)―in these words:

"הוא היה בעל קומה ובעל גוף ומשהו סופר. אף על פי שהעיד על עצמו שמאמין באמונת השיתוף לא היה מאמין שיש אדם מישראל שמאמין כך. ואם בא אצלו יהודי להשתמד היה שואל אותו מה ראית להמיר את דתך. אם אמר לו עני הוא ואין לו במה להתפרנס נותן לו שכר ומוסיף לו הוצאות הדרך שיסע ללונדון וישתמד שניה ויקבל שכר כפול. ואם אמר לו מתוך הכרה רוצה להמיר את דתו גוער בו בנזיפה ואומר לו צא וספר לגויים, אני איני מאמינך. כך היה מספר לנו, כדי להתחבב עלינו, ולגויים היה מספר אחרת, כדי להתחבב עליהם. משנתייאש למצוא חן בעיני אלוקים ביקש למצוא חן בעיני אדם. אבל כל שאין רוח המקום נוחה הימנו אין רוח הבריות נוחה הימנו. ישראל מחמת שהתכחש בעמו ובאלהיו, והנוצרים מחמת שלא היו מאמינים לו אמונתו."

"He [the Apostate] was large and tall and somewhat of a writer, although he testified to himself that he believes in the faith of sharing, he would not believe that there is any man in Israel who believes so. And if a Jew came to destroy himself, he’d ask him, “What are your reasons that you want to change your religion?” If the Jew told him that he is poor and has no way to make a living, he would give him a salary and add the expenses for travel to go to London and destroy his religion again, and get a double payment. And if the Jew told him out of all consciousness, “I want to change my religion,” he would tell him off and say, “Go and tell the goyim, I don’t believe you!” That’s how he’d tell it to us, to make us like him, and to the goyim he’d tell it another way, to make them like him. When he had grown desperate of being loved by God, he asked to be loved by man. But any person with whom God’s spirit is disagreeable, then man’s spirit will not be agreeable with him either: Israel, because he denied his people and his God, and the Christians because they didn’t believe in his faith." [Trans: Riva]

In 1898, Feingold built Feingold House on Jaffa Street in Jerusalem, near the Nahalat Shiv’a neighbourhood. The house was a three-story building, and according to the description in the Palestine Post, each floor had thirteen rooms (the number of the tribes of Israel) made in the shape of the letter L, with an inner courtyard where there was a rose garden. The inscription Shema Yisrael and Magen David are engraved on the gate of the building, and the verse from Isaiah, I have set watchmen on your walls, O Jerusalem, is engraved on the masonry. The house was used for residence and commerce, and became a thriving economic centre; on the second floor of the house was the first cinema in Israel, which opened in 1912. However The building got a bad name, and people referred to it as The House of the Apostate. Agnon writes in Tmol Shilshom that since God-fearing peoples avoided ‘the Apostate’s’ house, the apartments were cheap to rent, and was not required a year in advance, as was customary in Jerusalem. This is how Agnon describes the house:

"כל הבית מיושב ומדוייר. למטה חנויות ומחסנים ומרתפים, ועליהם חדרי דירה שפתחיהם פתוחים לתוך החצר, וגזוזטרא של ברזל מקיפה אותם כמין מ"ם סתומה. ומשפחות ורווקים ורווקות דרים שם. מקצתם בעלי אומנויות אינטליגנטיות ומקצתם אין להם אומנות מסוימת, אבל מוכנים לכל עסק. מקצתם אמנים וסופרים ומקצתם קרובים לאמנות ולספרות. וביניהם כובעניות ותופרניות, שידיהן עושות מלאכה ולבן פונה לאותו איני יודע מהו."

"The whole house is settled. Downstairs, shops and warehouses and cellars, and above them apartment rooms that open into the yard, and an iron balcony surrounds them in the shape of a final mem [a square]. And families and bachelors and spinsters live there. Some of them of the intellectual arts, and some of them without a specific art but ready for any business. Some of them are artists and writers, and some of them are close to art and to literature, and between them are hat-makers and seamstresses, with their hands doing the work and their hearts turned to I know not what." [Trans: Riva]

Feingold bought and sold real estate, and was involved in construction projects. He also came into partnership with Itamar Ben-Avi―the son of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the reviver of the Hebrew language―as owner of the newspaper which Ben-Avi edited, HaZvi. The arrangement brought the newspaper economic momentum, which stemmed mainly from advertisements for stores owned by Feingold, and from the printing of the newspaper at the Mitzpe Press owned by Feingold. On the back page of each issue were advertisements for various Feingold businesses―English beds, iron beams, large and small notebooks, all of which could be purchased ‘on very favourable terms’ from Feingold. But Ben-Avi's partnership with the “apostate” drew much criticism and mocking and, after six months, the partnership fell apart in acrimony. Although some believed this to be the result of interfering by Feingold in the content of the newspaper, Ben Avi denied this, putting it down to an obscure incident in which the Russian consul demanded that Feingold divest himself of the newspaper, and Feingold, being a Russian citizen, was forced to obey him. Feingold, however, claimed that the Ben Yehuda family “attached to him like a leech and sucked his blood,” and due to their blackmail, he was forced to terminate the partnership. A few days after the closure of HaZvi, in February 1910, the Ben-Yehuda family began publishing a new newspaper, HaOr (The Light), assuring its readers that it would “not depend on any man and any institution ...” Feingold, in his Hebrew name, Shlomo Yaffa Zahav, attacked the family and its newspaper in the Herut newspaper.

The same year, Feingold began publishing a newspaper called HaEmet (The Truth), in the spirit of the newspaper, La Vérité, which he had previously published in Paris. It was sold in English, French and Hebrew versions, and suffered severe attacks from its press rivals. Itamar Ben-Avi was again drawn into the acrimony when Yitzhak Yaakov Yellin, editor of Moriah, attacked HaEmet, hinting that his rival, Ben Avi, was the real publisher, renting his services to ‘missionaries’ for the sake of his greed.

With the outbreak of World War I, Feingold, who was a Russian citizen, was forced to move to Alexandria, where he opened a laundromat, and continued publication of HaEmet from there. Below the paper’s title the strapline read, “A weekly paper founded in Jerusalem 1910, temporarily published at Alexandria, Egypt.” Most articles in the paper were written by Feingold who signed under the pen name, Ketem Paz, and in English, Yaffez. In 1915 Feingold’s wife, Elizabeth, died. The newspaper finally ceased to appear in 1916.

Construction in Palestine

In March 1919, Feingold and Palmer returned to Jerusalem, turning to real estate again. Also around this time, Feingold met Yehudit Simcha Schindel, an English Jewess born in 1881, daughter of Rabbi Hermann Schindel of the Ramsgate Jewish community, and the pair got married. But let us go back to 1904. Already in that year Feingold had established houses for rent―known as the Feingold Houses―and a hotel, Bella Vista, at Manshiya in Jaffa. He was the first to try to exploit the tourist potential of the beach in the area, several years before the establishment of Tel Aviv.

Feingold and Palmer now spent part of their time in Tel Aviv. Some say that the figure standing alone in photographer, Avraham Soskin’s famous picture (public domain) documenting the lottery of the plots of land (Hagralat HaZedafim), is Feingold, who shouts to the gatherers, “You’re crazy, there is no water!” Although likely apocryphal, the story is retold in a book of short stories about Tel Aviv, Light and Magic, written by Rubik Rosenthal. Feingold's assets in Tel Aviv were managed by Feingold's younger brother, Isaac.

The Bella Vista Hotel was one of the most luxurious in the country. During the First World War, the Turks confiscated it and turned it into a detention centre, which was used to imprison foreign nationals awaiting deportation.

In 1919 Feingold began the construction of three houses at the intersection of Lilienblum and Nahalat Binyamin streets in Tel Aviv: a house for Margaret Palmer, a mansion for himself, and the post and telegraph office on the corner, as well as the Sussmanowicz hotel nearby. The buildings were designed by architect Yitzhak Schwartz (Shen-Zur) and were highly-ornamented with domes, spires and sculptures. In the late 1920s, Feingold also purchased a house at 33 Balfour Street. In 1930, Feingold ran into financial difficulties and was declared bankrupt. The same year the post office moved to a new central post office building at 132 Allenby Street. All four of Feingold’s properties in Tel Aviv were put up for auction and subsequently demolished, the post office building being purchased by a bank, demolished and replaced with a new building.

Left: Feingold's private home, on Nahalat Binyamin Street in Tel Aviv, in the early 1920s [credit: American Colony (Jerusalem), public domain]

Right: The Post and Telegraph House and, to the right, Alice Palmer's House, Tel Aviv, 1920s [credit: unknown photographer, public domain]

In 1925, the city of Afula was established, designed by the architect Richard Kaufman. Feingold believed that Afula had commercial potential, and in October 1925 laid the cornerstone for the city’s main commercial building, stating that he also intended to build residential buildings, a post office, a police station, and a school. In the end, only the commercial building, Feingold House, was built, becoming the main administrative building of the city in its early days. A cinema was established on the second floor― the Aviv Cinema―which operated during the Mandate and the early days of the state, continuing until the late 1970s under the name Neve Or. The building was restored at the beginning of the twenty-first century by the municipality and remains in commercial use.

Elizabeth Hotel

Feingold's last major construction project was in Tiberias, and so we come full circle to the subject of this blog, the Elizabeth Hotel.

At the end of World War I, the British encouraged the expansion of the Jewish settlement in Tiberias by establishing neighbourhoods outside the walls of the Old City. For this purpose, the Ahuzat Bayit Association was established and initiated the laying out of a new Jewish neighbourhood on the slopes of the north-western mountain, called Kiryat Shmuel―in honour of the first High Commissioner of Palestine, Herbert Samuel. The design for the neighbourhood was completed by Scottish town planner Sir Patrick Geddes FRSE and Joshua Salant in 1921. The design included residences, public buildings, gardens and a hotel.

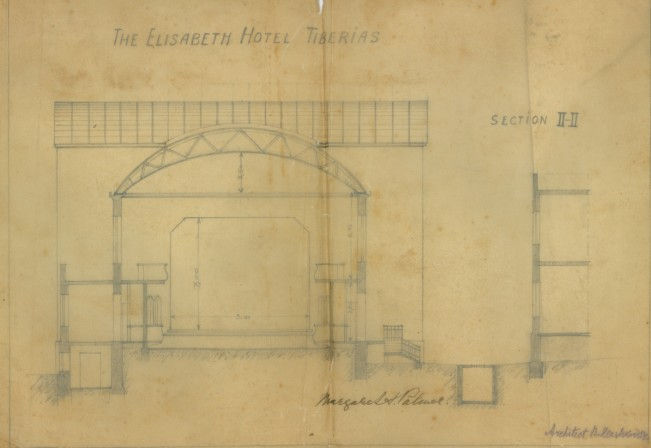

Into the picture steps Feingold who, in the mid-1920s, decided to settle in Tiberias. He joined the Ahuzat Bayit Association in 1926 and purchased a corner plot of five dunams, number 239, on which he planned to build a hotel. Feingold commissioned architect Zelig Axelrod, but after the two quarrelled, he transferred the work to Aharon Schwarzblatt initially, but after the Mandatory inspected the building and found it differed from the approved plans, architect Dov (Boris) Hershkovitz―designer of Hadassah Hospital in Tel Aviv's Balfour Street, the City Council House in Rothschild Boulevard and Dizengoff House from where the State was proclaimed―became involved. The design became larger and larger, entailing further taxes and charges from the Mandatory planning authority. This was to be a large and luxurious, modernist-style hotel. The hotel was constructed by Solel Boneh, who hired workers from Tiberias and the Gordonia Zionist youth movement. When priority was given to the Gordonia youth, conflict broke out between the workers, ending with fighting, which the police had to break up, making arrests.

On 1 February 1929, the hotel―originally called the Feingold Hotel but renamed the Elizabeth Hotel or, more properly, the Elizabetha Haven of Rest and Auditorium, after Feingold’s late wife―was opened in the presence of senior figures of the Mandatory and clergy, Jews and Arabs, headed by the High Commissioner of Palestine, Sir John Chancellor. Perhaps the most luxurious hotel in the north of Palestine, its three floors were designed for hospitality and entertainment. It boasted an opulent ballroom with parquet floor and red velvet chairs―the first such hall in the country to be built without supporting pillars by way of a coffered concrete ceiling. The eastern wing of the hotel sported a dome and included 80 guest rooms. The public rooms included, as well as the hall, a lounge with a luxurious marble fountain, an ornate dining hall, smoking rooms and smartly-decorated bridge and billiard rooms. In the western wing there was a theatre with 500 seats, a balcony and boxes.

The complex soon became an attraction for all the residents of the Jordan Valley and the Lower Galilee, and a meeting point for local people on Saturday nights and in the week. People came to the theatre to enjoy famous plays and films―later there was a second, independent cinema, the Aviv Cinema, just across the street, increasing the choice of entertainment―or simply to meet up with friends, dine, or spend time in the hotel lobby.

Feingold and his second wife, Yehudit, lived at the hotel, as did Margaret Palmer. Though it was a popular resort and meeting-place among Israelis and tourists, Feingold failed to run the hotel as a commercial success, and in 1931 he and Palmer filed for bankruptcy; he continued living there afterwards, running it on behalf of its new owners. However the same year Feingold’s and Palmer’s properties―in Tel Aviv, Jaffa, Tiberias, Afula, an unfinished house in Ramat Gan and plots in Jerusalem, Tiberias and Ramla―were put up for auction. In 1934, the hotel was taken over by the Salzman Pension and became very popular with British officers and soldiers. Shortly afterwards, Margaret Palmer moved from Tiberias to live in the German Colony in Jerusalem, where she died on 9 January 1944, aged 98. She is buried in the Templar Cemetery in Emek Refaim.

Shlomo Feingold died on 16 August 1935, and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tiberias. The Rabbinical Court in Tiberias divided his estate between Margaret Palmer, Yehudit Feingold, and other relatives and nephews. He had no children. Yehudit Feingold continued to live a life of poverty, earning a living from a liquor stand in the hotel courtyard, until her death in 1953. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tiberias.

Up until 1948, British officers continued to live at the hotel, but after the British left, it was abandoned and fell desolate. In 1949 the hotel was renovated and brought back to life as Hotel Genossar and a cinema opened in the theatre wing, called the Elisheva (Elizabeth) Cinema, was opened. The walls were painted with large murals by Hanna Lerner, who also painted a mural in the President’s House in Jerusalem. However Hotel Genossar did not last, closing in the late 1960s, although the cinema limped on into the 1980s; the place stood deserted for many years until, in August 2001, a fire burned down almost all but the shell of the place and the landmark silvered dome collapsed. Although arson was suspected, the deed was never investigated, and no suspects were arrested.

Hotel Genossar (Gennesareth) in a postcard of the early 1950s (left) and 1960s (right) [public domain]

After the fire the complex was recognized as a heritage site by the Council for Conservation of Heritage Sites in Israel; together with the Municipality of Tiberias they tried to initiate the renovation of the hotel, but the scheme came to nothing.

At the time of writing (2020) the hotel remains a wreck, but is destined for partial preservation (the front of the existing building) alongside the construction of a multi-purpose building that includes hotel, commerce, and a 20-25 floor residential building. According to the new owners of the hotel plot, Piedmont Enterprises, their project, named Michelangelo Towers, will reanimate one of the most unique historical buildings in Israel, making Hotel Elizabeth one of the most iconic and magnificent building in Tiberias.

Feingold's legacy remains in a number of magnificent buildings, which still stand in the city centres of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Afula and―though in ruins currently―Tiberias. In the early years of the Zionist enterprise in Palestine, Feingold was an investor and entrepreneurial force, bringing livelihood to the Jews of the country, and development to its major towns, even though his ties to the cult of British Israelism, his suspected and still unclear apostacy, the unclear nature of his relationships with the three women in his life―Margaret Palmer and his two wives, Elizabeth and Yehudit, left him a figure of fun or even hatred, with a somewhat dubious reputation. It has even been written that, during the years that he and Yehudit lived with Margaret in the Elizabeth Hotel in Tiberias, he was bigamously married to both of them, though there is no evidence of this. Nevertheless all this has conspired to ensure that Feingold has never been memorialized, is little-known and not much written about. Neither did his work receive any official recognition from the State of Israel or the Zionist movement. On his gravestone in the Jewish cemetery in Tiberias, the following words are engraved, and it has been written that, despite the acrimony of their relationship, Itamar Ben-Avi believed that the words reflected Feingold’s life’s work: “A loyal pioneer to the Land of Israel and its inhabitants.”

Below is a slideshow of the hotel today.

Comments